By Samuel Wrest

As the economies of emerging Asia continue to develop, the region’s tax rates are becoming increasingly influential. From the perspective of Asia’s governments, taxes can be used to either ensure that investments flow in to their own jurisdiction, or as a means to subsidize government spending. Conversely, from the standpoint of companies and individual wage earners, they can help determine whether a particular jurisdiction suits their business model and occupation.

There are numerous taxes which will be applicable for foreign businesses and wage earners in Asia, including corporate income tax (CIT), individual income tax (IIT), withholding tax, and indirect taxes such as value added tax (VAT) and goods and services tax (GST). Understanding how these various taxes function is integral both for companies wishing to access Asia’s emerging markets, and individuals looking to work in the region.

In this excerpt from our latest Asia Briefing magazine, we provide an introduction to Asia’s rates of taxation. We explain what these taxes are, briefly discuss how they apply to Asia, and conclude by taking a look at how Asia’s countries compare in the World Bank’s latest ease of paying taxes rankings.

![]()

A corporate income tax (CIT) is a tax levied on the profits of a company, most commonly by a given country’s state government but also occasionally by its provincial governments.

In Asia, the rate of CIT varies considerably from nation to nation, with some jurisdictions fixing it at as little as 17 percent and others at a massive 40 percent. The rate of CIT that a country enforces can be informed by a myriad of factors, including the priorities of government (whether more emphasis is placed on state revenue or investment), the nature of its economy (how reliant it is on foreign investment), the country’s size, and its level of development.

The definition of what a corporation is and whether it is subject to CIT tax varies from country to country, with several jurisdictions in Asia imposing CIT on legal entities that others would not. For example, Malaysia’s CIT hinges on an entity’s residence – on whether control and management of the corporation is actually within Malaysia – but this concept has almost no bearing in Hong Kong, where CIT is often imposed regardless of residence. For more details on a company’s eligibility for CIT in a given Asian jurisdiction, see our CIT chart in the second section of the 2015 Asia Tax Comparator.

![]()

In essence, an indirect tax adds to the price of a purchasable product or a payable service, thereby increasing the cost of that product or service and causing consumers to indirectly pay its rate of taxation. This differentiates indirect tax from other forms of taxation, such as corporate income and individual income tax; both of which require a business or an individual to pay the applicable amount directly to a government.

Indirect taxes differ from other taxes in several other ways. For instance, because they are attached to purchasable items and services generally, they are not reduced or increased according to an individual’s income or a corporation’s profits.

In Asia, countries employ either a value added tax (VAT) or goods and services tax (GST) as their system of indirect taxation, although some do not have an indirect tax at all. Several countries have either reformed or only just introduced their indirect tax systems in the past ten years, including both India and China. The tax revenue generated is commonly shared between central and local governments.

![]()

A withholding tax is a tax that is kept back from an employee’s salary and subsequently paid directly to the government. Withholding taxes are commonly employed by countries throughout the world to help combat tax evasion.

Countries in Asia typically divide withholding tax into dividends, interest and royalties payments, with the amount of each varying considerably in each country. India, for instance, does not have any withholding tax on dividends, but has a 30 percent tax on royalties.

![]()

An individual income tax (IIT) is a tax levied on all wage earners within a given jurisdiction. With the exception of Brunei and Cambodia, the former having no IIT in place and the latter a fixed 20 percent rate, the Asian countries highlighted in this magazine all employ a progressive IIT system wherein an individual is taxed according to how much they earn. This results in individuals with a higher salary being taxed at a greater rate than those with a lower one. Rates vary wildly across Asia, with some countries capping their maximum IIT at as much as 45 percent and others at as little as 17 percent.

![]()

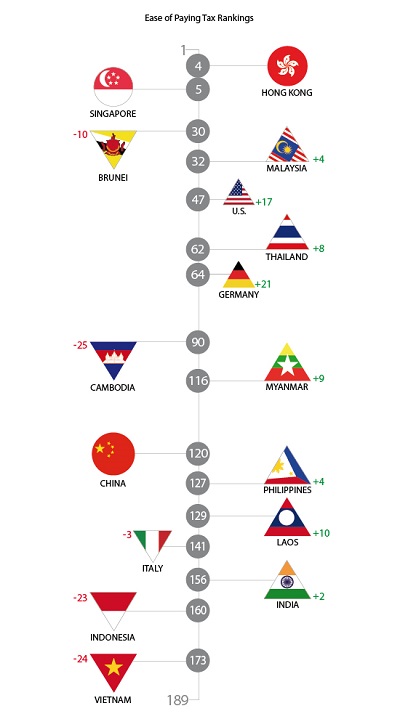

One of the key contributing factors to the World Bank’s “Doing Business” rankings is the ease of paying taxes, which takes into account the time, total tax rate and number of payments necessary for a company to pay off all of its tax obligations. Here we provide the rankings for the 13 countries highlighted in this magazine, as well as the U.S., Germany, and Italy.

Compared to 2014’s rankings, there have been several significant changes to the ease of paying taxes in Asia. India has moved up two ranks, and Indonesia and Vietnam have dropped 23 and 24 ranks respectively. In the context of the 13 countries highlighted in this magazine, this means that India has moved from being the worst ranked country last year to 11th position, whilst Indonesia and Vietnam have dropped to be the two worst ranked.

The top five positions have also seen a slight change. Thailand has moved up eight ranks overall and Cambodia has dropped 25. As a result, Thailand is now the fifth ranked country out of the 13 and Cambodia the sixth.

This article is an excerpt from the December issue of Asia Briefing Magazine, titled “The 2015 Asia Tax Comparator“. In this issue, we compare and contrast the most relevant tax laws applicable for businesses with a presence in Asia. We analyze the different tax rates of 13 jurisdictions in the region, including India, China, Hong Kong, and the 10 member states of ASEAN, which consists of Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. We also take a look at some of the most important compliance issues that businesses should be aware of, and conclude by discussing some of the most important tax and finance concerns companies will face when entering Asia. This article is an excerpt from the December issue of Asia Briefing Magazine, titled “The 2015 Asia Tax Comparator“. In this issue, we compare and contrast the most relevant tax laws applicable for businesses with a presence in Asia. We analyze the different tax rates of 13 jurisdictions in the region, including India, China, Hong Kong, and the 10 member states of ASEAN, which consists of Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. We also take a look at some of the most important compliance issues that businesses should be aware of, and conclude by discussing some of the most important tax and finance concerns companies will face when entering Asia. |

![]()

Manufacturing Hubs Across Emerging Asia

In this issue of Asia Briefing Magazine, we explore several of the region’s most competitive and promising manufacturing locales including India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. Exploring a wide variety of factors such as key industries, investment regulations, and labor, shipping, and operational costs, we delineate the cost competitiveness and ease of investment in each while highlighting Indonesia, Vietnam and India’s exceptional potential as the manufacturing leaders of the future.

The Gateway to ASEAN: Singapore Holding Companies

The Gateway to ASEAN: Singapore Holding Companies

In this issue of Asia Briefing Magazine, we highlight and explore Singapore’s position as a holding company location for outbound investment, most notably for companies seeking to enter ASEAN and other emerging markets in Asia. We explore the numerous FTAs, DTAs and tax incentive programs that make Singapore the preeminent destination for holding companies in Southeast Asia, in addition to the requirements and procedures foreign investors must follow to establish and incorporate a holding company.

An Introduction to Tax Treaties Throughout Asia

An Introduction to Tax Treaties Throughout Asia

In this issue of Asia Briefing Magazine, we take a look at the various types of trade and tax treaties that exist between Asian nations. These include bilateral investment treaties, double tax treaties and free trade agreements – all of which directly affect businesses operating in Asia.