Japan’s decision to re-adopt nuclear power clears uncertainty that has hung over Asia’s LNG market since the Fukushima meltdown. Only a portion of Japan’s nuclear reactors are expected to restart, however, meaning the market will remain tight in the near-term as Japan continues to rely heavily on LNG imports.

Op-Ed Commentary: Mallory LeeWong

On April 11, the Japanese government approved a new energy plan that backs nuclear power and restarts reactors that have been idle since the 2011 Fukushima disaster. Only 14 – less than one-third – of Japan’s 48 idle nuclear reactors are expected to eventually come back online, however, due to tighter safety regulations and political, economic and seismic obstacles. This means that in the near- to mid-term, Japan’s demand will likely remain strong for fossil fuel substitutes, including coal, oil and, in particular, liquefied natural gas (LNG).

The government’s plan calls nuclear an “important baseload power source,” meaning that nuclear provides a critical, constant flow of power to the country’s grid to meet minimum energy demand.

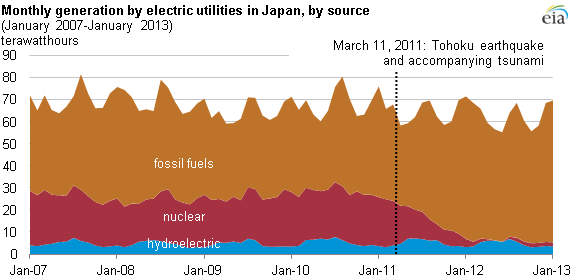

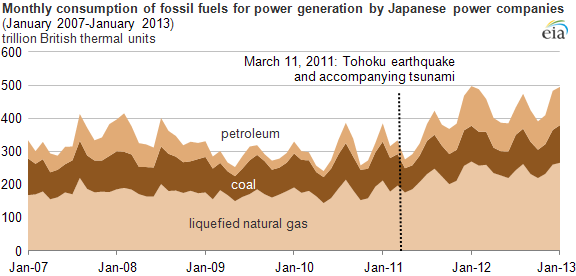

Currently, Asia accounts for 70 percent of global LNG trade and Japan is the world’s largest LNG importer, relying on imports to supply almost 95 percent of its natural gas needs. In 2011, Japan shut down all of its nuclear power generation capacity, which supplied one-third of energy consumed. Since then, the country’s LNG imports have risen by nearly 30 percent, and Japan’s share of global LNG consumption has climbed from 33 percent in 2011 to 37 percent in 2012.

According to Japan’s Ministry of Finance, during the year ending in March 2014 Japan imported a record high of 87.73 million tonnes of LNG, pushing the country’s trade deficit to an unprecedented 13.75 trillion yen (US$134.34 billion).

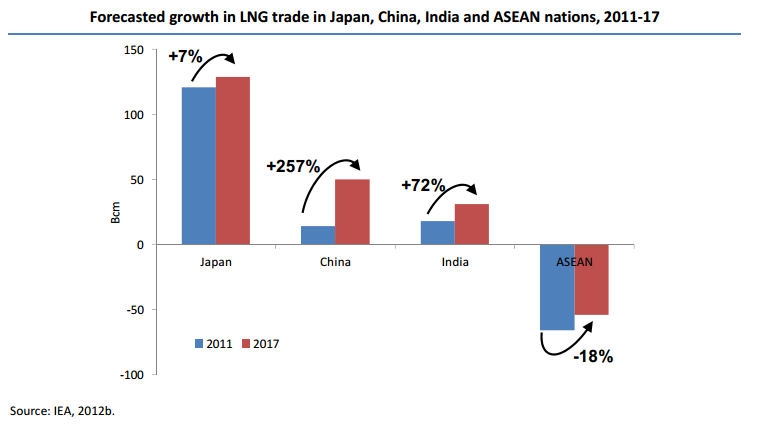

The Asian LNG market is expected to remain tight through 2020 due to long infrastructure build-outs and regulatory approval processes, and booming demand driven by China, Japan, South Korea and India that will put upward pressure on prices.

China’s demand for LNG will be the key swing factor in determining how high regional prices rise. The country’s demand is projected to rise sharply to the end of the decade, outweighing slight downward pressure on prices from Japan’s restart of reactors.

Rising LNG prices in Asia have been felt fiscally throughout the region, particularly by Japan. Since 2010, Northeast Asian LNG spot prices have increased from about US$10-12 per MMBtu (million British thermal units) to US$15-16 and sometimes even US$17-20 per MMBtu. These high prices are threatening the competitiveness of Japan’s industry and exports.

High oil prices are also driving LNG prices in Asia. Asian LNG is typically oil-linked, and prices are based on the average Japanese Customs Cleared Crude (JCC) price: the average price of Japan’s customs-cleared crude oil imports, also known as the “Japanese Crude Cocktail.”

The economic burden of operating without nuclear power and depending heavily on imported fossil fuels has driven Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) government to push for the resumption of nuclear power generation. His administration views nuclear as an indispensable affordable, low-carbon and secure source of indigenous energy.

Meanwhile, Japanese companies have leapt to secure new sources of LNG from the United States, Canada, Australia, Russia and Eastern Africa that will enter the market in the next five to ten years.

LNG flowing from the U.S. shale gas boom is of particular interest to Japanese and other East Asian buyers, which see U.S. LNG exports as a new cheaper alternative to oil-linked Asian market prices. U.S. LNG prices are linked to the price of domestic U.S. natural gas delivered by Henry Hub, the natural gas pipeline in Louisiana that serves as the official delivery point for natural gas futures sold on the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX).

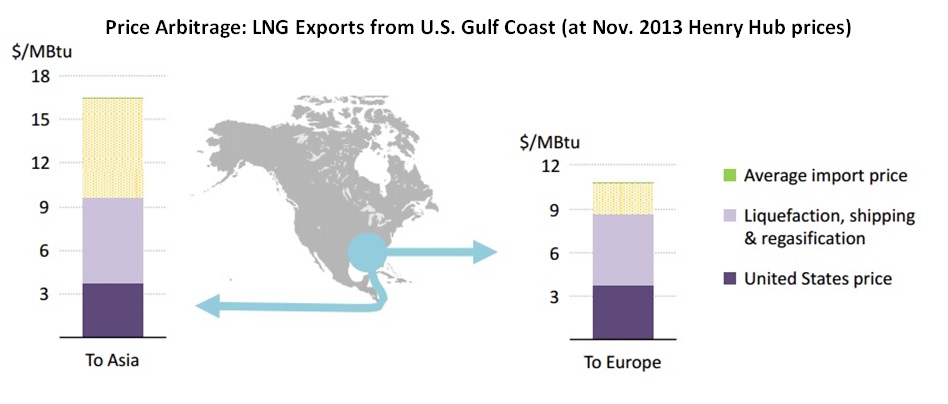

Based on current Henry Hub prices hovering around US$4 per MMBtu, the potential for price arbitrage is large. After accounting for liquefaction, transmission and shipping costs, companies could make about US$6 per MMBtu exporting U.S. LNG to Asia from the U.S. Gulf Coast, and about US$8 per MMBtu from the West Coast.

U.S. LNG exports to East Asia will likely remain competitive through 2020 while the Henry Hub price remains below US$6 per MMBtu.

The U.S. economy and oil and gas industry stand to benefit tremendously by turning terminals recently built to import LNG into exporting facilities. While LNG exports would slightly increase domestic gas prices for downstream and end users, exports could significantly reduce the U.S. trade deficit and strengthen the dollar in the long term.

There are currently over two dozen applications awaiting federal approval to build export facilities as companies rush to cash in on the price differential in East Asia and beat out Russian LNG. These include applications to export to countries with which the United States has free trade agreements (FTAs) and non-FTA countries such as Japan and China. The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) can restrict natural gas exports to non-FTA countries, however, since shipping away these resources might not be in the public interest.

In 2012, Cheniere Energy Inc. received federal approval to construct Sabine Pass, the first major U.S. LNG export terminal. Sabine Pass exports are scheduled to come to market in 2015.

In February, DOE authorized the export of LNG via the Freeport export terminal, a US$10 billion export facility to be built in Texas that will reach commercial operation by 2018.

Japanese utilities Osaka Gas and Chubu Electric have committed to investing US$589 million each for a combined 50 percent equity stake in the first train of Freeport’s liquefaction facility, and agreed to purchase 2.2 million mt/year of U.S. LNG with no restrictions on use or shipping destination, potentially allowing for trading put-call options internationally to enhance supply flexibility.

These Japanese companies are the first to link Freeport LNG to Henry Hub prices.

Beyond 2020, the Asian LNG market will depend primarily upon China’s demand for the chilled gas, which may fall as a result of domestic shale gas development and pipeline supply coming online from Myanmar, Central Asia and potentially Russia’s Far East.

Japan’s decision to re-adopt nuclear has also been met by strong local opposition, with those against nuclear in Japan outnumbering those in favor by about two-to-one, according to recent polls.

Mallory LeeWong is an M.A. Candidate in International Economics at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) specializing in East Asian and U.S. energy policy and markets. She has over two years of experience in China, including in the energy and environmental sectors.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of Asia Briefing Ltd.