A doubling of India’s workforce capabilities and decreasing age dependency ratio suggest the country may soon catch up with China’s manufacturing capabilities.

Op-Ed Commentary: Chris Devonshire-Ellis

The phenomenal rise of China over the past two decades has often eclipsed that of India, whose economic growth and development has appeared sluggish by comparison. The reasons given for this are many, yet mainly centred around the superiority of the one party state in decision making and planning over that of democratic structures, the poor state of Indian infrastructure and, to some extent, the bureaucratic nature of Indian administration.

All of these arguments carry some weight, but often lost amongst these reasonings are the demographic factors. In this degree, China has enjoyed a demographic boom in terms of the ability of its population to drive an emerging economy in a manner that India has not.

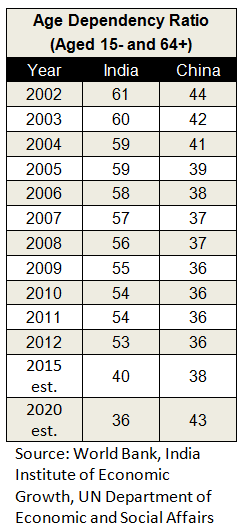

If we examine age dependency ratios, in which the number of dependents every 100 workers has to support is measured, we note that China in 2002 had a demographic of 44 dependents to every 100 workers, dropping to 36 in 2010. This has enabled Chinese workers – and the state – to create new independent wealth. India, in contrast, had an age dependency ratio of 61 in 2002, dropped to 53 in 2010 – a heavy burden for India to bear in terms of wealth creation.

As both China and India have relatively poor social welfare systems, this means that Chinese nationals have, over the last decade or so, been able to amass more wealth than Indian nationals – they had less of a social burden to carry, and is one of the drivers behind the creation of China’s new middle class. Now 250 million, China’s emerging middle class is expected to reach 600 million by 2020.

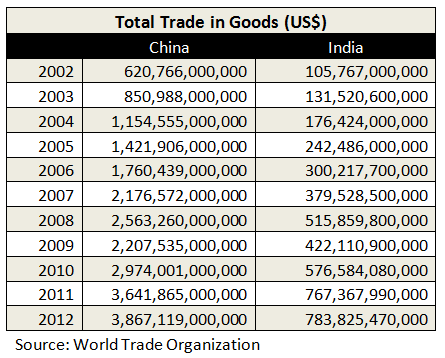

This demographic dividend has been reflected in the growth of China’s total trade over the same period when compared to India. Since 2002, Chinese total trade expanded from US$620 billion to US$3.86 trillion in 2012. Interestingly, India kept pace with that growth rate, albeit from a lower base – India’s trade grew from US$105 billion to US$783 billion during the same time frame, being roughly equivalent to a fifth of total Chinese trade during this period.

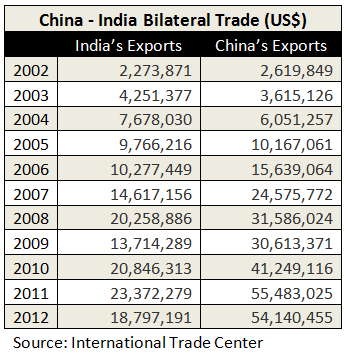

However, coupled with this, bilateral trade relations between the two nations have developed in leaps and bounds. From a base of US$5 billion in 2002, bilateral trade stands at US$73 billion in 2012, a huge increase way beyond the natural growth patterns of each individual economy as they have developed.

Put simply, India has matched China’s trade growth rates over the past decade, while bilateral trade has increased exponentially. In fact, the China-India trade corridor is one of the most dynamic in the world, and may become even more so.

RELATED: Intra-Asian Trade Flows to Help Global Economy Top US$100 Trillion by 2020

Faced with an increasingly demanding and aging population, while at the same time experiencing increased production costs, China is desperate to source cheap product manufacturing for its own market. Step forward India – which is one reason China has offered to fund up to 30 percent of the country’s infrastructure development costs – it needs Indian made products in its own markets to replace the labour-intensive industries it is leaving behind. Giving all of that to India allows China to concentrate on its real industrial goal – to emulate, overtake and eventually become superior to Japan in hi-tech and new innovative industries.

It is what happens next in terms of Indian growth and wealth creation that gets interesting. China’s workforce as of 2013 is 920 million, and is expected to increase slightly to 956 million by 2028, after having gone through a period of some decline. India’s workforce, however, is set to nearly double from today’s 478 million to 971 million by 2028.

This is set to have a massive impact on worker availability in India, and on the global manufacturing dynamic. With wages (including social welfare) about five times higher in China than in India, India is now poised to inherit the worker demographic that China has been enjoying and that has helped make the nation prosperous.

RELATED: Asia’s Improving PMI Performance Against China The New Normal

India’s age dependency ratio is set to drop from 53 today to just 36 by 2020 – the same as China right now. But during the next seven years, China’s age dependency ratio will increase to 43. China’s population will find more support is required from them to look after an aging population, while India’s will start to become more wealthy with decreasing social burdens to cater for. Add to this a massively increasing Indian work force, and we end up with a persistent age differential between China and India over the next decade – Indian workers being a constant ten years younger than their Chinese counterparts.

The implications of this are profound. Young wealthy Chinese will have to start paying more to support their aging in-laws, and will be purchasing more Indian made products. Young Indians will start to amass more wealth. With a doubling in size of India’s workforce over the next two decades, and with wage levels expected to remain just 20 percent of those in China, global manufacturing will start to find India increasingly attractive.

While no one expects India to overtake China’s overall economic might, what is apparent is that the demographics suggest that it is India, and not China, whose growth rates and wealth will increase the more rapidly over the next two decades.

This year, foreign investment into India has been slow. An election is taking place, and foreign investors want to see the make-up of the new government, and the policies it will usher in, before ramping up FDI inflows. Yet, whichever political party gets in, they stand to inherit an India poised for the first time in decades to take strong strides in economic development and reform. All the next Indian government has to do is create policies that allow India’s young workforce to be productive. That includes lowering tax rates, decreasing trade barriers and continuing to improve the national infrastructure.

If this can be done, it draws to a close the regional mandate that it is China alone that has the rule over twenty years of sustained development and economic growth. With little else to do than stand back and let the demographics fulfill their potential, it is about to become India’s turn to succeed China in high sustainable growth rates and wealth creation.

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the Founding Partner of Dezan Shira & Associates – a specialist foreign direct investment practice providing corporate establishment, business advisory, tax advisory and compliance, accounting, payroll, due diligence and financial review services to multinationals investing in emerging Asia. Since its establishment in 1992, the firm has grown into one of Asia’s most versatile full-service consultancies with operational offices across China, Hong Kong, India, Singapore and Vietnam, in addition to alliances in Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines and Thailand, as well as liaison offices in Italy and the United States.

For further details or to contact the firm, please email asia@dezshira.com, visit www.dezshira.com, or download our brochure.

You can stay up to date with the latest business and investment trends across Asia by subscribing to Asia Briefing’s complimentary update service featuring news, commentary, guides, and multimedia resources.

Related Reading

Expanding Your China Business to India and Vietnam

Expanding Your China Business to India and Vietnam

In this issue of Asia Briefing Magazine, we discuss why China is no longer the only solution for export-driven businesses, and how the evolution of trade in Asia is determining that locations such as Vietnam and India represent competitive alternatives. With that in mind, we examine the common purposes as well as the pros and cons of the various market entry vehicles available for foreign investors interested in Vietnam and India. We also examine the advantages of using Hong Kong and Singapore as corporate bases to reach out to Asia’s emerging markets. Finally, we comment on how the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership will affect both China-based and Vietnam-based manufacturers.

Taking Advantage of India’s FDI Reforms

Taking Advantage of India’s FDI Reforms

In this edition of India Briefing Magazine, we explore important amendments to India’s foreign investment policy and outline various options for business establishment, including the creation of wholly owned subsidiaries in sectors that permit 100 percent foreign direct investment. We additionally explore several taxes that apply to wholly owned subsidiary companies, and provide an outlook for what investors can expect to see in India this year.

Trading with India

Trading with India

In this issue of India Briefing, we focus on the dynamics driving India as a global trading hub. Within the magazine, you will find tips for buying and selling in India from overseas, as well as how to set up a trading company in the country.

Trading With China

Trading With China

This issue of China Briefing Magazine focuses on the minutiae of trading with China – regardless of whether your business has a presence in the country or not. Of special interest to the global small and medium-sized enterprises, this issue explains in detail the myriad regulations concerning trading with the most populous nation on Earth – plus the inevitable tax, customs and administrative matters that go with this.

India-China Strategic Dialogue Revolves Around Indian Infrastructure Development

India to Boost Infrastructure Investment Through Trust Fund

Developing Asian Manufacturing Capacity from a China Operational Base