Op-Ed Commentary: Chris Devonshire-Ellis

When it comes to making comparisons across Asia, and especially the various regional economies, a difficulty is in choosing a commodity familiar to all within this massive region. Typically, housing prices, cost of labor and even mobile phone penetration or the famous Mars Bar Index are used to demonstrate how economies and regional prices vary against the same product. Having given this some thought, while trying to maintain an Asian flavor in our 2014 comparison, we decided to choose a dish prevalent across Asia – Stir-Fried Prawns. It is perhaps the one dish that can be found from Northern China to Southern India, and all points in-between, and is therefore a reasonable barometer to try and ascertain how Asian consumers differ in their local costs of consuming what to hundreds of millions of people is either a tasty lunch or dinner dish.

When it comes to making comparisons across Asia, and especially the various regional economies, a difficulty is in choosing a commodity familiar to all within this massive region. Typically, housing prices, cost of labor and even mobile phone penetration or the famous Mars Bar Index are used to demonstrate how economies and regional prices vary against the same product. Having given this some thought, while trying to maintain an Asian flavor in our 2014 comparison, we decided to choose a dish prevalent across Asia – Stir-Fried Prawns. It is perhaps the one dish that can be found from Northern China to Southern India, and all points in-between, and is therefore a reasonable barometer to try and ascertain how Asian consumers differ in their local costs of consuming what to hundreds of millions of people is either a tasty lunch or dinner dish.

That said, the data collected was subject to some regional variations – recipes and ingredients differ to some degree as of course do the prices in restaurants serving them. Accordingly we have tried to standardize the dish as basic Stir-Fried Prawns, keeping the variety of local ingredients used to a minimum. The vast majority were prepared using simple garlic and/or chili. Additionally, we have researched mid-market restaurants (excluding 5 star hotels) who have listed the dish online on their restaurant websites – although often in their regional language. For ease of comparison, we have converted the local cost of each dish into US$ dollars.

Asia is of course a huge producer of prawns for the global market, meaning the cost of prawns locally are likely to reflect those countries with a significant prawn aquaculture industry. Seventy-five percent of all prawns consumed globally originate in Asia, meaning the product is an important benchmark for where the manufacturing industry in Asia is starting to become more expensive, and where it remains relatively cheap. The prawn farming industry is relatively labor intensive, meaning wages impact upon the end price of the product on your plate, as does property prices – we have quoted Stir-Fried Prawns as served in restaurants – meaning they have had to factor in the cost of rent. The cost of the product, wages, supply chain and rent – plus, of course, profit taking – will all factor into the consumer cost of what is, after all, a pan-Asian, yet common delicacy.

Another potential cost variable is in the different types of prawns. Thailand is the world’s largest exporter of marine prawns, with the global market consuming only two varieties of prawn – Litopenaeus vannamei (pacific white shrimp) and Penaeus monodon (giant tiger prawn) – which account for roughly 80 percent of all farmed marine prawn. There is just one other species sold globally, and that is the giant river prawn – (Macrobrachium rosenbergii), which is a fresh water variety. China produces 90 percent of the world’s demand of fresh water prawn – yet by the time it reaches your plate there is little to choose from between marine and fresh water prawns in either cost or taste. This means that the cost data is consistent when the product being compared only comes in limited varieties globally.

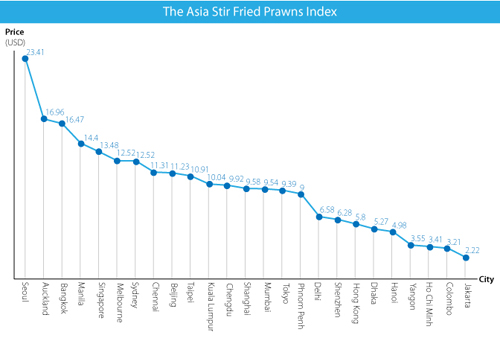

The 2014 Stir-Fried Prawn Index is below, listed in US$ per serving and by country (click to enlarge):

It is surprising that Seoul has by far the most expensive Stir-Fried Prawns in Asia – we didn’t see that coming. Yet in both Japan and Korea, Chinese dishes tend to attract premium prices, and for both, super freshness is the key. We suspect that the high prices of prawns in these countries – as well as for Singapore, has to do with high rents as well as the freshness required, meaning cold storage and supply chain costs will be more. The same is also true of Melbourne, Sydney and Auckland, where strict importation and quality standards will impact upon the end user’s price. However, the cost of a plate of prawns in Tokyo represents better value than the cost of labor and rent would suggest is feasible – meaning perhaps that restaurants sell the dish as a loss-leader to attract customers who would then buy more expensive seafood.

In India and Delhi, prices were about the same as in China’s second tier cities – a sign that China’s general consumer wealth is becoming equivalent to that of India’s tier one cities. So far, so predictable. But Bangkok and Manila both seem expensive – especially as Thailand is traditionally a major exporter. However, prices in Thailand shot up in 2013 due to disease spreading throughout their prawn farming industry – Thai exports of prawn last year dropped by 50 percent as a result – and the Philippines were a major buyer. Both are members of ASEAN and limited their customs duties on the intra-prawn trade corridor – but supply problems in Thailand pushed up prices in both countries.

India’s position smacks of their apparent atrophy; where being aligned, even in cities such as Delhi and Mumbai, to be content to have the same standard of living and disposable income as cities such as Shenzhen and Chengdu. It may come as a shock, but China’s second tier cities – and some third – have already overtaken India’s primary urban centers in terms of quality and wealth, and this shows in the price of a dish of prawns. The Stir-Fried Prawn Index should be a warning to India to shape up to the China challenge or be left behind as second-class consumer citizens in Pax Asiatica.

A lesson here for buyers (of any product in Asia, and especially perishables) is to have second options close at hand – just in case a problem such as in Thailand occurs. This rings especially true of China, whose global dominance of the fresh water prawn export market could also become a supply issue – especially given mounting pollution problems in the country. This potential bottle-neck mirrors in fact what happened with the global supply of rare earths – China’s dominance suddenly became apparent and, when declining to increase exports, caused manufacturing problems elsewhere, most notably in Japan, where rare earths are used in semi-conductors. Reliance, therefore, on just one country as a major supplier carries a downside, and in the world of prawn exports, just one major incident or virus could wipe out stocks or suppress demand. Prawn farming, it appears, is not without some major risks as an industry.

China meanwhile showed its rise as a consumer nation – we polled five mainland cities and all came roughly in the middling expensive bracket. Perhaps more surprisingly, Hong Kong, despite its higher rent and labor costs, was able to put Stir-Fried Prawns on the table at far less a cost than on the mainland. We suspect a prawn price fixing cartel in Mainland China may be responsible for keeping prices artificially high – especially, as has been noted, because China is a primary global producer. The cost of Stir-Fried Prawns across China is also indicative, yet again, of those steadily rising domestic costs. It is not a cheap destination any more – not even for a dish of prawns.

At the bargain end of the table lies Vietnam – who has recently been upgrading its prawn farming capacity and is seeking to challenge Thailand’s prior global dominance in the industry. As Thailand’s exports dropped, Vietnam’s rose – a timely reminder of how strategic planning in industry can reap rewards. That extra capacity has manifested itself in cheap domestic Stir-Fried Prawns – aided also by the countries’ relatively low labor costs and rent. Sri Lanka is another country who has been getting into prawn aquaculture. Like Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, that extra capacity is having an impact on the price of the dish available in Colombo, Sri Lanka’s capital.

But best of all, the award for cheapest prawns in Asia goes to Jakarta. ASEAN’s free trade, a booming domestic economy, low rent and labor costs have all factored together to enable the city to take prime position in terms of the cheapest Asian city to enjoy a plate of Stir-Fried Prawns. It may come as no surprise to those who follow operational costs in Asia, but in the cost of getting a plate of Stir-Fried Prawns to you, our dear readers, good value can be found in Vietnam and Indonesia, while China is becoming middle income expensive. That, to some extent, clarifies the new Asian destinations for export manufacturers, and holds out the suggestion that China’s reforms are indeed leading it to become a middle class consumer market of significant value.

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the Founding Partner of Dezan Shira & Associates – a specialist foreign direct investment practice providing corporate establishment, business advisory, tax advisory and compliance, accounting, payroll, due diligence and financial review services to multinationals investing in emerging Asia. Since its establishment in 1992, the firm has grown into one of Asia’s most versatile full-service consultancies with operational offices across China, Hong Kong, India, Singapore and Vietnam as well as liaison offices in Italy and the United States.

For further details or to contact the firm, please email asia@dezshira.com, visit www.dezshira.com, or download the company brochure.

You can stay up to date with the latest business and investment trends across Asia by subscribing to Asia Briefing’s complimentary update service featuring news, commentary, guides, and multimedia resources.